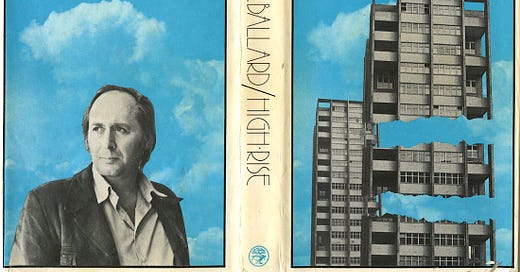

Ballard’s High Rise: An unconscious diagram of a mysterious psyche

Can people's behavior be influenced by a certain type of dwelling? Why do civilizations descend into chaos?

How the Myth of High Began

Today it is easy for us to imagine an ultra-technological skyscraper, but when Ballard wrote High-Rise, this was not the case. The Home Insurance Building, built in 1885 by William Le Baron Jenney (1832-1907), was the first skyscraper in history. It was only 10 floors, but for the first time the structure was made of steel, invisible from the outside. Skyscrapers have created the myth of the great metropolis since 1854, when Elisha Graves Otis (1811-1861), a farmer's son from Vermont, built the safety brake for elevators and exhibited it at the New York World's Fair. The birth of the safety elevator laid the conceptual and technological groundwork for skyscraper construction.

Babel

The myth of verticality is babelic. It is man reaching for the sky, as when the Twin Towers were built in New York. They gave form to man's passion for the extraordinary, the oversized, the uncontrollable. Unfortunately, the events of September 11th put a dramatic and horrifying face on all this (and it certainly wasn't just two planes that brought down the towers, but that's another line). When I read High-Rise, all of that came to mind. But Ballard's High-Rise is in London. Today, with The Shard, One Canada Square, Manhattan Loft Gardens, Spire London, there are at least ten skyscrapers in the City... The skyscraper in Ballard's novel is a building, but it is also a non-place, cut off from the outside world, where the inhabitants are as if on another world, both physically and mentally.

It’s a mistake to imagine that we’re all moving towards a state of happy primitivism. The model here seems to be less the noble savage than our un-innocent post-Freudian selves, outraged by all that over-indulgent toilet-training, dedicated breast-feeding and parental affection – obviously a more dangerous mix than anything our Victorian forebears had to cope with. Our neighbours had happy childhoods to a man and still feel angry. Perhaps they resent never having had a chance to become perverse…

(From High Rise, 1975)

When the protagonist is a Condominium

In Ballard’s novel High-Rise, the protagonist of the story is a condominium, which becomes transfigured as the Tower of Babel. It contains more than two thousand apartments on forty floors, located in the eastern suburbs of London. Over the story, it evolves from an elitist, self-sufficient structure into the final stage of a kind of civilizing process. In this process, a society governed by increasingly oppressive norms develops self-destructive tendencies that eventually lead to chaos.

The three perspectives

The social degeneration unleashed in the Condo is told from the alternating perspectives of three tenants: Robert Laing, Richard Wilder, and Anthony Royal, who represent the three social classes present in the building. The way in which the flats are used makes the division into social classes particularly clear. The residents with the lowest social status occupy the first nine floors, and their parking spaces are located farthest from the building. Richer residents occupy the top nine floors and have easy access to elevators and parking. The tenth and thirty-fifth floors contain a supermarket, restaurant, bank, and swimming pool. The remaining nineteen floors are occupied by the middle class.

Alternatively, their real needs might emerge later. The more arid and affectless life became in the high-rise, the greater the possibilities it offered By its very efficiency, the high-rise took over the task of maintaining the social structure that supported them all. For the first time it removed the need to repress every kind of anti social behavior, and left them free to explore any deviant or wayward impulses. It was precisely in these areas that the most important and most interesting aspects of their lives would take place. Secure within the shell of the high-rise like passengers on board an automatically piloted airliner, they were free to behave in any way they wished, explore the darkest corners they could find. In many ways, the high-rise was a model of all that technology had done to make

possible the expression of a truly ‘free’ psychopathology.

An unconscious diagram of a mysterious psyche

The three inhabitants who tell the story are very dissimilar. Robert Laing is a doctor, and he lives on the twenty-fifth floor, apathetic to the fate of others ( ironically, he is a doctor) and busy practicing a kind of voluntary exile that would "save" him from the rest of humanity. Richard Wilder, on the other hand, is a television producer who lives on the second floor with his wife and children. He wants to make a documentary about the psyche of people living in a high-rise, but he has an abrasive and instinctual personality, so much so that Ballard compares him to an animal, a primitive warrior, and then to a little boy. Finally, there is Anthony Royal, the building's architect, who lives on the top floor with his wife and children, a hyperrational individual who summarizes the significance of the condominium's dynamics as "an unconscious diagram of a mysterious psyche." Of the three, Royal (as his last name suggests) is of the ruling class, but he needs a cane to walk as a result of a car accident that also disfigured his forehead. This brings to mind another Ballard character, Vaughan from the novel Crash, both of whom become "architects of chaos" through car accidents.

The Triggering Event

However, it is not violence that sets everything in motion, but a seemingly random event. One morning, a bottle of sparkling wine falls from one of the upper floors onto Dr. Laing's balcony. The doctor picks up the pieces and, in an "aberrant gesture," throws them from the balcony. This is the action that begins the frenzy: the condo becomes a shattered heap, garbage is thrown everywhere, furniture is broken up to make barricades or bonfires, fixtures are damaged, and corpses are abandoned. Simple quarrels become frightening hostilities. Social conventions are broken, and the high-rise becomes a foreshadowing of what any metropolis can become: a place of fear and unbridled instincts.

Utopian and dystopian

High-Rise is not about architecture or the consequences of a bad architectural structure, it goes much further. It is about the social consequences of using a certain kind of technology in construction to realize the utopia of the perfect residence, which, when inhabited by imperfect people, becomes a dystopia. There is no hyper-technology or explicit science fiction in this novel, but there is the science fiction journey into the human psyche. The meaning ascribed to the building is utopian, in fact Wilder calls it "our suspended paradise," which effectively removes it from the real urban context and isolates it, but the chaos that results from this detachment from reality turns the architectural design dystopian and sets back (in evolutionary terms) the human being who inhabits it.

Five floors were without electricity. At night the dark bands stretched across the face of the high-rise like dead strata in a fading brain.

The Critical Mass

The first chapter is called "Critical Mass": critical mass is the amount of material necessary to trigger the reaction in nuclear weapons. Ballard tells us right away: The tranquility of the apartment building is illusory, and its inhabitants are ready to explode like bombs. But what is the path, the human and social path, that leads to the dystopia of mass destruction?

Is it in the inner space (the human psyche)?

Is it in the outer space (the high-rise)?

Is it in the enclosed inner space (the individuals within the high-rise)?

Can people's behavior be influenced by a certain type of dwelling? Why do civilizations descend into chaos? Or, rather, why do individuals degenerate into chaos when they are placed in certain conditions? Any attempt to form social bonds is destroyed by the narcissistic orientation of the characters trapped in Ballard's high-rise. Each narcissism destroys the other, demonizes him and makes him guilty. Narcissism is itself dystopian. In Ballard's novel, prosperity becomes an antisocial fuse; the absence of real problems or challenging situations leads to boredom, and boredom leads to narcissism and paranoia, devaluing people.

The global High-Rise

Ballard was skeptical of utopias, and he proves it again in this novel, but once again his dystopian vision is a kind of warning, a view of one urban landscape among the myriad possibilities of other urban landscapes. And perhaps, today in 2023, we should ask ourselves if we are not all trapped in a dystopian global high-rise right now.

İsmail Serdar Altaç. (2020). "Community purified by com-mutiny: Remapping the path to dystopia in J. G. ballard’s High-Rise." at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342410816

Ballard, James Graham (1975). "High-Rise".

Ballard, James Graham (1973). "Crash".

McHale B. (1987). "Postmodernist Fiction." Routledge, London-New York.