What if the Library of Congress was a Quantum Reality?

Hugh Everett's Many-Worlds can be found in the Library of Congress. They are there, within easy reach. And the Library contains and protects them.

Dont’ worry! I’m not to write the history of the Library of Congress, that’s not my job, and there are plenty of scholars and historians who are very good at that. But I love books and I love libraries, and today, April 24, I want to remember how lucky we are. Because having a place to keep books is always a great blessing.

“The institution that serves as the national library of the United States is perhaps more fortunate than its predecessors in other countries. It has Congress as its godfather. This stroke of good fortune has made it perhaps the most influential of all the national libraries in the world.”

[S.R. Ranganathan, ‘The Library of Congress Among National Libraries,’ ALA Bulletin 44 (October 1950): 356.]

A pillar of American civilization

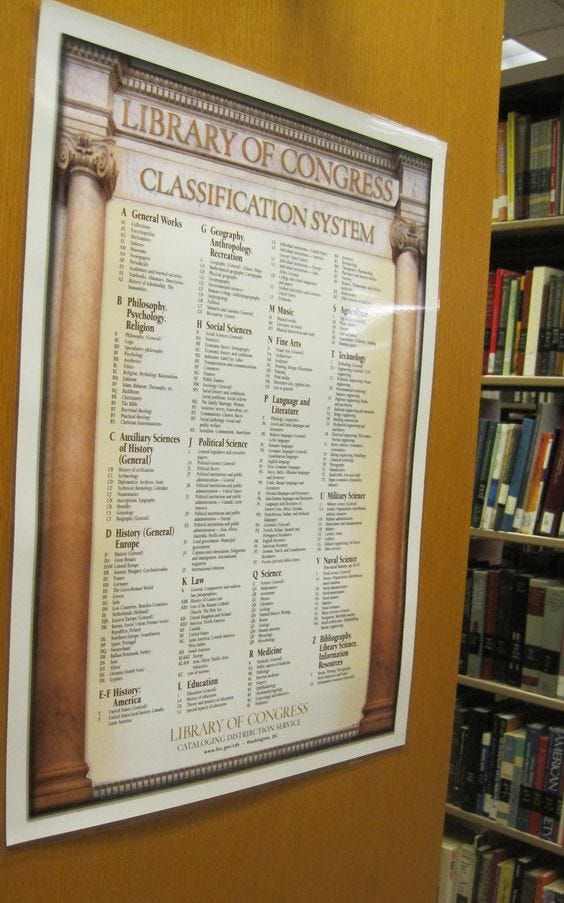

Millions of books in over four hundred different languages. Millions of books. But can you imagine it? Of course you can imagine it, there is no need to imagine it, it is reality. The Library of Congress is a pillar of American civilization. When it was founded it was a legislative library, but after World War II it became an international resource of unprecedented and unparalleled scope. Its history is intertwined with the history of the United States, according to the designs and aspirations of three men-Thomas Jefferson, Ainsworth Rand Spofford, and Herbert Putnam.

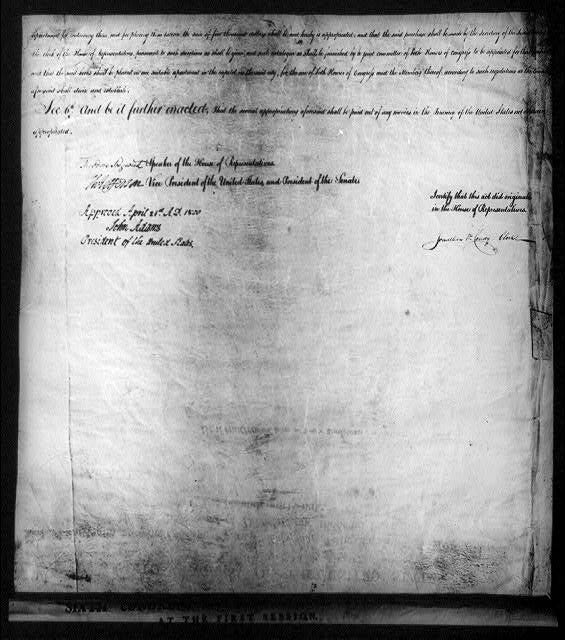

On April 24, 1800, President John Adams passed a bill appropriating $5,000 for the purchase of “books necessary for the use of Congress.” The first books, ordered from London, arrived in 1801 and were stored in the U.S. Capitol, the Library's first location. On January 26, 1802, President Thomas Jefferson passed the first law defining the role and functions of the new institution. This measure created the office of Librarian of Congress and gave Congress, through a Joint Committee on the Library, the authority to establish the rules and regulations of the Library. [here]

And how do we get to quantum mechanics?

Through Hugh Everett’s Many-Worlds Theory. Okay, I know, it seems fool, but give me a chance! Everett conceived the idea of the Universe "splitting" into different versions of itself in 1955 at Princeton University. But he was not taken very seriously. In the late 1960s, however, the idea was taken up and promoted by Bryce DeWitt (University of North Carolina), who wrote: "Every quantum transition that occurs in every star, in every galaxy, in every remote corner of the Universe divides our local world on Earth into a myriad of copies of itself.”

Talking in quantum terms, this means that whenever a choice is made, the wave function (the physical-mathematical trend of the probable positions of particles at a given time) that identifies the subatomic behavior of the Universe divides, generating another Universe, thinner than the first (because total mass is always the same).

Let’s game with the philosophical implications

Well, we have to stop thinking about mathematical abstractions and just focus on the philosophical implications. That's what makes the game work. Imagine this: Every time you make a choice (or don't make a choice), reality splits because every possibility continues to exist in an alternate one. Let's say you decide to stop reading this article, right now, at this very moment, Everett said that in another "world," you would have continued reading; in an another one you wouldn't have even started the article. And in one of those worlds, I probably didn't even write it (okay, now you're thinking about moving to the world where I didn't write. I know!). Alternatives. Worlds that present alternatives to choices made or not made.

The Library of Congress is a Quantum Reality!

A library is a place where, in quantum (philosophical) terms, time and space overlap to contain different space-time realities. Books are quantum boxes, because every story, every narrative, every essay contains choices and thus opens up alternatives. So I like to think of Hugh Everett's Many-Worlds as being in the Library of Congress. They are there, within reach. And the Library contains and protects them. Many worlds. Every book is a world. Every essay a hypothesis of reality. Every novel a construction of an alternate world. All the stories around us (short or long; written or not) are space-time portals and allow us to take overlapping positions in time and space. I swear I am excited as I write this. But isn't it extraordinary? When I walk into places like the Library of the Congress I feel that the principles of quantum mechanics really become a human matter. Because physics is about our being in the world and our connection to creation. To the universe. To God. And also to the great libraries.

Crazy cool, I tell you.

Sorry if this article is a bit silly. But I had a lot of fun, and I hope it amused you, too! Thanks and happy birthday to the Library of Congress.

Insights - Sites

Jefferson's Legacy: The Functions of the Library of Congress, Past and Present

On These Walls. Inscriptions and Quotations in the Buildings of the Library of Congress

10 Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About The Library Of Congress

Insights - Books

John Y. Cole, (2018). America's Greatest Library: An Illustrated History of the Library of Congress. GILES.

John Y. Cole, (2008). On These Walls: Inscriptions & Quotations in the Library of Congress. Scala Arts Publishers Inc.

Andrew Pettegree, Arthur der Weduwen, (2021). The Library: A Fragile History. Basic Books.

David Deutsch would enjoy this!

I loved this post! And I absolutely love the Library of Congress and have both visited it and passed it on the way to work many many times. I love your idea of books being a force multiplier and hence quantum in nature! It’s actually brilliant. It kind of reminds me of Borges’ Library of Babel and his hexagonal rooms and infinite knowledge, except there, the librarian becomes suicidal thinking that the knowledge is useless. Not the LOC!